Urban Preparedness Review 2023

WHO Tool for Reviewing Health Emergency Preparedness in Cities and Urban Settings

Urban areas, especially cities, have unique vulnerabilities that need to be addressed and accounted for in health emergency preparedness. An unprepared urban setting is more vulnerable to the catastrophic effects of health emergencies and can exacerbate the spread of diseases, whilst they are also very often the frontline for response efforts. This has been seen in past disease outbreaks, as well as during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is therefore crucial that health emergency preparedness in cities and urban settings is addressed through contextualized policy development, capacity building, and concrete activities undertaken at the national, subnational, and city levels.

Last update on 9 February 2024

This review tool has been developed to support the implementation of the global Framework for Strengthening Health Emergency Preparedness in Cities and Urban Settings. It is based on the operational guidance for national and local authorities that accompanies the Framework. It aims to support countries achieve a greater level of health emergency preparedness, by focusing on the unique challenges and vulnerabilities that exist at the city level, and ultimately lead to better national application of the International Health Regulations (2005).

Use of the Tool

The content of the self-review process in the online tool has been developed from the operational Guidance for national and local authorities. The guidance includes actions split into three categories:

1) For national and local authorize

2) For national authorities

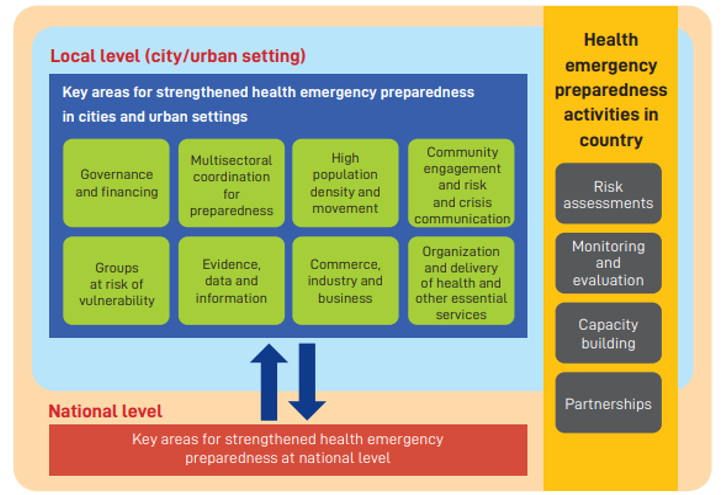

3) For local authorities and distributed across the eight sections from the Urban Preparedness Framework (below green boxes).

In the online Tool, each action is mapped to the IHR core capacities and presented as an element for review. Users of the tool are to review each action using the scoring criteria, considering the context of their country/city. In addition to the rating, there is a space to input any technical and capacity gaps, and elaborate qualitatively on the score given. The process has been developed after a review of the IHR JEE process and WHO REMAP methodology. The tool also includes capabilities mapped across the HEPR 5 C’s that were developed as part of the horizontal HEPR workstream on ‘Settings’, of which urban settings were designated as one of 3 key settings for HEPR. These are presented for review in the same format as the Urban Preparedness actions. Visual graphs will be populated as the tool is filled out on a ‘Dashboard page’, showing average scores of each of the 8 sections, average scores of all actions related to different levels of authority (national/local), and across IHR core capacities.

Review Core Pillars

Reviews across 9 core pillars can be assessed by 5 levels

Core Pillar 1

Governance

Core Pillar 1 : Governance

Governance for Urban Health Emergency Preparedness -

Governance and financing are both key to effective health emergency preparedness. Focusing on preparedness at the sub-national level (such as the city/urban level) adds a layer of complexity from a governance perspective. It requires robust and effective mechanisms by which the different levels of government involved (e.g., national, regional, local) can coordinate, and a clear delineation of roles, responsibilities and accountabilities. Due to the nature of emergencies, these may differ from ‘peacetime’, and it is important that systems are ready to adapt for response when necessary. Any existing legislative gaps need to be identified and closed. The multiple layers of governance involved may also complicate financing, as budget lines, financing flows, and the distribution of funds may be different in an emergency. This is further complicated if there is a discrepancy between political agendas at different levels of governance. It is therefore important that mechanisms are in place to ensure funds can be released and redistributed as necessary in an emergency, without delays caused by the extra layers of governance involved.

Key challenges include:

A lack of political will to strengthen preparedness in cities and urban settings because of political differences, competing interests and short-term prioritization.

Governance mechanisms often do not allow for, or facilitate, the meaningful engagement of all levels of government in emergency preparedness planning and response.

Roles and responsibilities between national and local governments, as well as other stakeholders, are often not clearly defined in relation to preparedness for health emergencies.

Gaps tend to exist in the availability or use of legislative and coordination mechanisms for preparedness across different levels of government, with surrounding areas and with other cities.

Core Pillar 2

Financing

Core Pillar 2 : Financing

Financing for Urban Health Emergency Preparedness -

Adequate and sustained financing is important to ensure that capacities for health emergency preparedness as part of national health security agendas are also built at local levels. This is especially since this is where prevention, detection and response activities take place, and particularly in urban settings, where the majority of the population and unique capacities (e.g. airports as points of entry) are found. Financing is needed for building strong and resilient health systems that are necessary to absorb the shock of a health emergency and reduce disruption to essential health services. Many capacities crucial to preparedness can only be built over time, requiring sustained commitment and funding. Countries should therefore ensure that an appropriate proportion of funding is allocated to these longer-term activities that focus on the building of sustainable capacities (e.g. such as upskilling of the workforce, training to improve national surveillance, health information management and risk communication, and essential logistic requirements).

Key challenges include:

Competing priorities for limited budgets lead to insufficient funds for city governments and local actors for preparedness activities.

Short-term thinking in funding allocation and distribution leads to prioritisation of ‘quick-wins’ as opposed to investment in longer-term, sustainable preparedness needs .

Budgeting is predominantly at national levels and the access to and release of funds for cities for preparedness and response is slow.

Core Pillar 3

Multi-sectoral coordination for preparedness

Core Pillar 3 : Multi-sectoral coordination for preparedness

Multisectoral coordination for Urban Health Emergency Preparedness -

Strengthening health emergency preparedness at the urban level requires the support of multiple sectors and partners beyond health at all levels – from global to national, subnational, and local levels, including within cities and urban settings. Coordination across sectors and partners is vital to ensure coherence in preparedness activities and increase resilience, and should include all actors, including the private sector and civil society. This requires the use of whole-ofgovernment and whole-of-society approaches, with coordination often coming from the highest level of each government, including the offices of city leaders (e.g., Mayors and Governors), as well as potentially mainstreaming preparedness across departments at the operational level.

Key challenges include:

There is often an inadequate appreciation of the broad potential impacts of health emergencies on other sectors, and an unwillingness of other sectors and stakeholders to be actively involved in preparedness

Stakeholders at the local and national level can often work in siloes and there is a lack of clarity on who should lead multisectoral coordination for health emergency preparedness at local levels.

A lack of mechanisms for coordination and communication between sectors and stakeholders for preparedness.

Sectors at the local level are often not adequately engaged in health emergency preparedness activities undertaken at, or coordinated by, national authorities

Capacities for multisectoral coordination are often lacking at both national and local levels, but in particular at the local/city level

Core Pillar 4

High population density and movement

Core Pillar 4 : High population density and movement

High population density and movement -

Cities and urban settings often contain large numbers of people, leading to high population densities and crowding where people live, play and work. This increases the chance of being in crowded situations and means that health emergencies can impact a larger number of people at once, especially when it involves infectious diseases. In epidemics, especially those spread by droplets or aerosols, this increases the risk of disease spread. This includes shared spaces and public areas with high human traffic or are frequently used, and public transportation. Crowded situations often found in cities and urban settings include mass gatherings such as religious events, concerts and sporting events, or poorly ventilated areas such as bars, nightclubs and entertainment venues. Other locations such as nursing/care homes, dense forms of housing, refugee camps and commercial venues such as shopping centres may also pose risks, as well as mass gathering events, that often take place within cities. Further, overurbanization has also led to a proliferation of informal settlements / slums emerging, where population densities also tend to be higher, and they also rely on communal and often inadequate WASH facilities. Mobility between the mobile populations existing in these congregation points and local/fixed populations also risks the further spread of communicable diseases.

In addition, cities and urban settings often serve as major transportation hubs, with large airports, ports and ground crossings that connect populations across the globe, and which present specific risks and vulnerabilities when health emergencies occur, as they may lead to an accelerated importation or exportation of diseases. Nonetheless, these transportation hubs also offer strengths to the cities and urban settings where they are placed, as they act as entry points for emergency response personnel and medical countermeasures.

Key challenges include:

National health emergency preparedness plans do not adequately account for the unique nature and challenges of cities and urban settings in implementation.

Insufficient incorporation of health emergency preparedness considerations in urban planning, architecture, and design, including the benefit of having healthy, open spaces accessible especially for vulnerable populations.

Reliance on congested public transport systems within cities may pose additional risks in health emergencies, especially during disease outbreaks, and such risks need to be mitigated.

Core Pillar 5

Community engagement, risk & crisis communication

Core Pillar 5 : Community engagement, risk & crisis communication

Community engagement and risk and crisis communication -

As health threats emerge at local levels, communities play an important role in health emergency preparedness and risk reduction. Community members participating from the earliest stages of policy and programme formulation help clarify local priorities, challenges, and pathways for practical and sustainable action. This requires sustained and meaningful community involvement (beyond just engagement), such as through community led-approaches, participatory governance mechanisms, social participation methods, and the co-creation of solutions. Often, there is insufficient engagement,

integration, and protection of communities in cities and urban settings in health emergency preparedness plans. Whilst engagement can be challenging for a variety of reasons, the perspectives whic they offer enhance policy and programme development and ensure effective translation and implementation. Doing so also engenders trust in governments and public systems at all levels. Effective involvement and engagement of communities cannot be achieved without effective communication, tailored to the respective specific target audience.

Key challenges include:

Insufficient representation and involvement of local governments and communities in health emergency preparedness policy development.

Ensuring better access to prompt, reliable and culturally appropriate avenues for risk communication, targeted specifically to different audiences.

Dealing with ‘infodemics’, including in particular the management of misinformation.

A lack of alignment and complementarity between national and local public health communication.

Core Pillar 6

Group at risk of vulnerabilities

Core Pillar 6 : Group at risk of vulnerabilities

Groups at risk of vulnerabilities -

Preparedness for a health emergency in an urban setting includes anticipating and preparing for vulnerabilities linked to the direct or indirect impact of all-hazards. For example, restricted movements risk livelihoods of those dependent on the informal economy, as well as may hinder timely access to health services. Countries and their local communities are as strong as their weakest link, and preparedness and response plans will not be as effective if the needs of vulnerable populations are not looked after. This includes building community resilience to the impacts of health emergencies. In this regard, trusted community leaders and civil society organizations including those with established initiatives in working with and supporting vulnerable populations, may serve as an important resource.

Key challenges include:

The needs of vulnerable persons and communities are not as well understood and integrated into preparedness plans and RCCE strategies and materials, and the capacities and capabilities of these groups can be maximized.

There tends to be insufficient continuous engagement and protection of vulnerable groups in cities before, during and after health emergencies.

There are often difficulties in identifying and accurately mapping the location of groups particularly at risk of vulnerabilities to health emergencies.

Core Pillar 7

Evidence, data and information

Core Pillar 7 : Evidence, data and information

Evidence, data and information -

Data represents a challenge to cities globally; sometimes it is missing or limited, or when available, fragmented, siloed, or outdated. However, local authorities of cities and urban settings often hold a wealth of data which should be used to strengthen health emergency preparedness and response. This includes but is not limited to, urban settlement data such as demographics, informal settlements and other vulnerable communities, housing and zoning, transport networks, public and private facilities and resources, emergency, disaster and risk management, for example evacuation routes, supply chains information on current and future hazards, vulnerabilities, capacities, and scenarios, and population demographics. Such information can help guide efforts to improve preparedness and build community resilience, including leveraging crowd sourced data or sentinel sites for surveillance and sense-making. Aside from event detection, it can help monitor impact and assess the uptake and effectiveness of response measures and recommendations. Further, health considerations, including needs for emergency preparedness and response, can be better integrated into designing and building sustainable cities for the future. Where possible, data should be disaggregated by sex.

Key challenges include:

There are many available sources of urban data, but they need to be prioritized, reshaped, integrated and used for risk assessment and health emergency preparedness planning.

Available data is often not routinely shared or made available between different levels of governance, in particular between national and local levels.

There are specific concerns around privacy and confidentiality in the collection, sharing, and use of local level data often needed to improve health emergency preparedness.

Local governments of cities and urban settings are not equipped to conduct data management and analysis.

Core Pillar 8

Commerce, industry and business

Core Pillar 8 : Commerce, industry and business

Commerce, industry and business -

Cities and urban settings are centres for commerce and many industries, employing large numbers of individuals. They are also responsible for places where groups of people spend a substantial amount of time each day. In addition to this, many local businesses are community-centred with good networks, relationships and local knowledge. Therefore, businesses and corporations can serve as a partner and resource for national and local governments in preparing for health emergencies, in particularly when it comes to innovating in order to better prepare, detect and respond to novel and emerging challenges posed by future and ongoing health emergencies. This can cover a broad range of areas, including risk communication and risk management. Examples include occupational health and safety, including prevention of zoonosis, infection and contamination of food at live animal markets; instituting remote working arrangements where possible, and implementing public health measures to reduce the spread of infectious diseases at the workplace where remote working is not possible; providing resources in an emergency, such as the repurposing of manufacturing plants to producing personal protective equipment and the reorganization of commercial spaces or services to accommodate public health measures; and supporting risk communication and public engagement, through both customers and employees, around public health measures. They are also important for maintaining logistics and supply chains for the continued provision of essential services, for example for food and medical supplies, or the repurposing of manufacturing plants and using hotel rooms for quarantine and temporary housing for the homeless. Furthermore, without engaging national and local private business and enterprises, it is not possible to achieve the adequate support to key workers, transport systems, reorganization of public spaces / business models that is needed in order to maintain business continuity and continue providing adapted business services to local communities during a health emergency.

Key challenges include:

Insufficient trust and willingness of both national and local governments and commerce and industry stakeholders to work together for better preparedness, but COVID-19 has demonstrated the need to engage the broadest set of stakeholders and the opportunities in new partnerships.

A lack of appropriate engagement and accountability mechanisms with different types of businesses and industry stakeholders in cities and urban settings for preparedness.

Core Pillar 9

Organization & delivery of health & other essential services

Core Pillar 9 : Organization & delivery of health & other essential services

Organization and delivery of health and other essential services -

Health systems, in particular the delivery of health services, play a critical role in preparedness, response and recovery for all types of hazards. These range from primary and community care to tertiary level hospitals. For example, surveillance, detection and notification; vaccinations to prevent outbreaks, including prophylaxis of major zoonotic diseases in animals; infection prevention and control to prevent further spread of disease; and treatment to save lives are all dependent on the health system. Urban settings, especially major cities, tend to hold a full suite of services that can include academic hospitals with health specialists, advanced diagnostics, medical equipment, supplies, and intensive care units, all of which are crucial capacity in an emergency.

However, there can also be huge disparities and gaps in access to services in urban settings, especially by those of lower socio-economic status and hard-to-reach populations, leading to unequal health outcomes, delays in event reporting and contact tracing.

Beyond health facilities, cities and urban areas also often host other critical infrastructure that needs to remain operational regardless of the emergency situation (e.g., PoEs, power and freshwater plants, security & safety services, communication & ICT infrastructure, financial organizations, and others). Given the breadth and variety of services that exist in cities, it is important that the organisation of services is also organised around health security objectives. This requires collaboration across services, and a holistic and multisectoral approach to service delivery.

Key challenges include:

Health and non-health essential services are not optimally organized or funded to support health emergency preparedness and response when needed.

Disruption to the delivery of essential services in cities during emergencies is frequent and needs to be minimized.

Urban health systems are often lacking the resilience needed in order to ensure continuity of services during and after an emergency.

Process of the mapping and review tool

1) Self Review

WHO supports the country and city in identifying focal points from national and city level, who will co-ordinate the self review process vis the online tool. The self review will be filled in by the relevant officials. WHO will provide distance support from HQ and RO, and in person support from the WCO during this phase. The self review stage includes use of the online review tool, mapping of urban specific HEPR capabilities, and mapping of infrastructure for health security.

2) In country workshop

WHO will work with the country and city to conduct a 2 day workshop to convene relevant stakeholders (both involved in the process and beyond) to discuss the results and outcomes of the self review. Space will be provided during the workshop to discuss or rectify any gaps or inconsistencies that may have arisen during the self review process, as well as to analyses and discuss the results, gaps and challenges identified, and how they can be addressed. The workshop methodology will also include an integrated After Action Review or Simulation Exercise component, which can help discuss the states of health emergency preparedness in a city through a practical example.

3) Technical support and follow up

WHO will work with the country and city to identify technical follow up activities that can be undertaken and supported by WHO or partners to address some capacity gaps identified during the process. This includes facilitating financing and partnerships with donors to address identified gaps on urban development and preparedness for health security.

Scoring Criteria for use in the review

The below table outlines the broad scoring criteria that should be used throughout the application of the tool. Generally, the levels refer to whether or not the actions and approaches in the statements occur, or the capacities needed in the context of each statement are in place or not. A comment box is provided at the end of each line to elaborate on the answer. The more further information provided in this comment box, the better informed the discussions will be once the tool has been applied, and the more appropriate the follow-up actions identified.

| LEVEL | EXPLANATION |

|---|---|

| Level 1 | Non-existent: This does not occur / the attributes of related capacities are not in place. |

| Level 2 | Limited: This occurs rarely / the attributes of related capacities are in the development stage (implementation may be planned, but is not yet in place). |

| Level 3 | Developed: This occurs occasionally / the attributes of related capacities are partially in place, however sustainability has not been ensured. |

| Level 4 | Demonstrated: This occurs frequently / the attributes of related capacities are in place. |

| Level 5 | Sustainable: This occurs sustainably / the attributes of related capacities are functional and sustainable. |

Who should be engaged in the review process?

The following stakeholders should be involved in the various stages of the review process.

| Area of Review Tool | Stakeholders to be involved |

|---|---|

| Review of preparedness | National authorities (MoH and other ministries as relevant); Sub-national authorities (municipal/city authorities); WHO (HQ, RO, CO) |

| Health Security infrastructure mapping | Sub-national authorities (municipal/city authorities); relevant national authorities (e.g Ministries of Planning, Development or Finance); WHO (HQ, RO, CO) |

| Technical Workshop | National authorities (MoH and other ministries as relevant); Sub-national authorities (municipal/city authorities); local institutions including NGOs; other relevant stakeholders at the national and city level; WHO (HQ, RO, CO); development partners working at the city level |